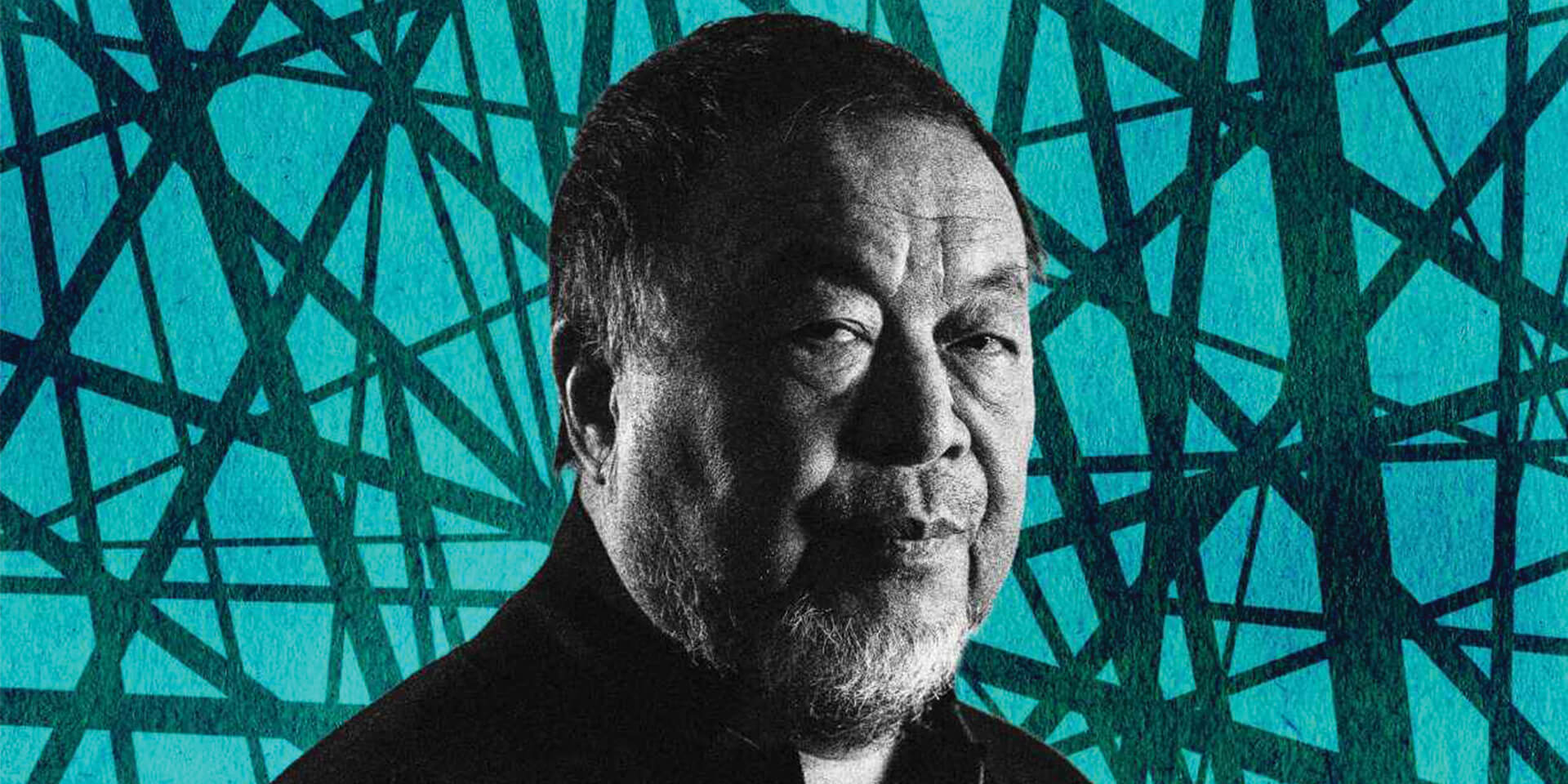

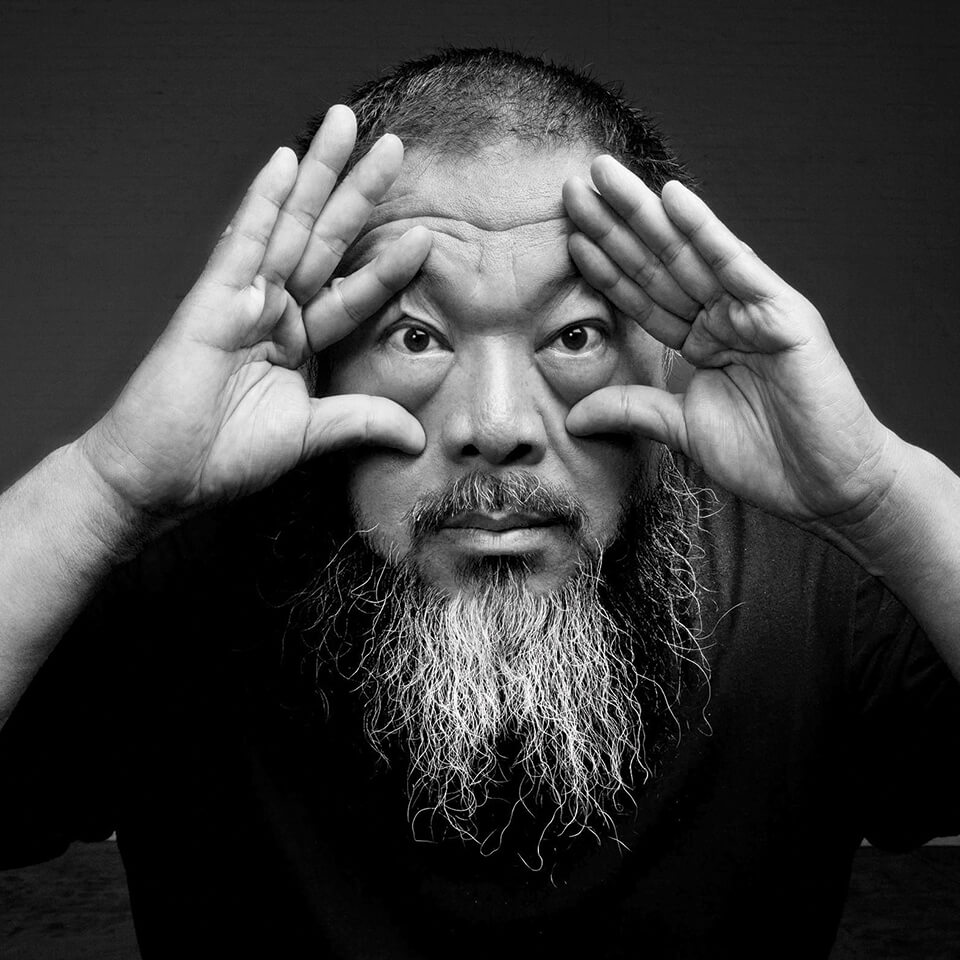

Captured and harassed by the Chinese government, artist Ai Weiwei makes bold works, unlike anything the world has seen. A year ago, the editors of ArtReview magazine named the Chinese dissident the most powerful artist on the planet. which was quite an unusual choice, so to say. Although his work doesn’t fetch the highest prices at auctions, his work is greatly admired despite critics’ beliefs to agree with the fact that he is a master who has transformed the art of his time. In China, Ai who is looked at as a valiant and unwavering commentator of the tyrant regime has been imprisoned, was not allowed to leave Beijing due to the laws imposed on him by the government and to date cannot travel anywhere without official permission grants. Subsequently, he has become a symbol of the battle for human rights in China, but not pre-eminently. He is too impetuous a figure to have constructed the moral gravitas of the great men of conscience who tested the authoritarian routines of the twentieth century.

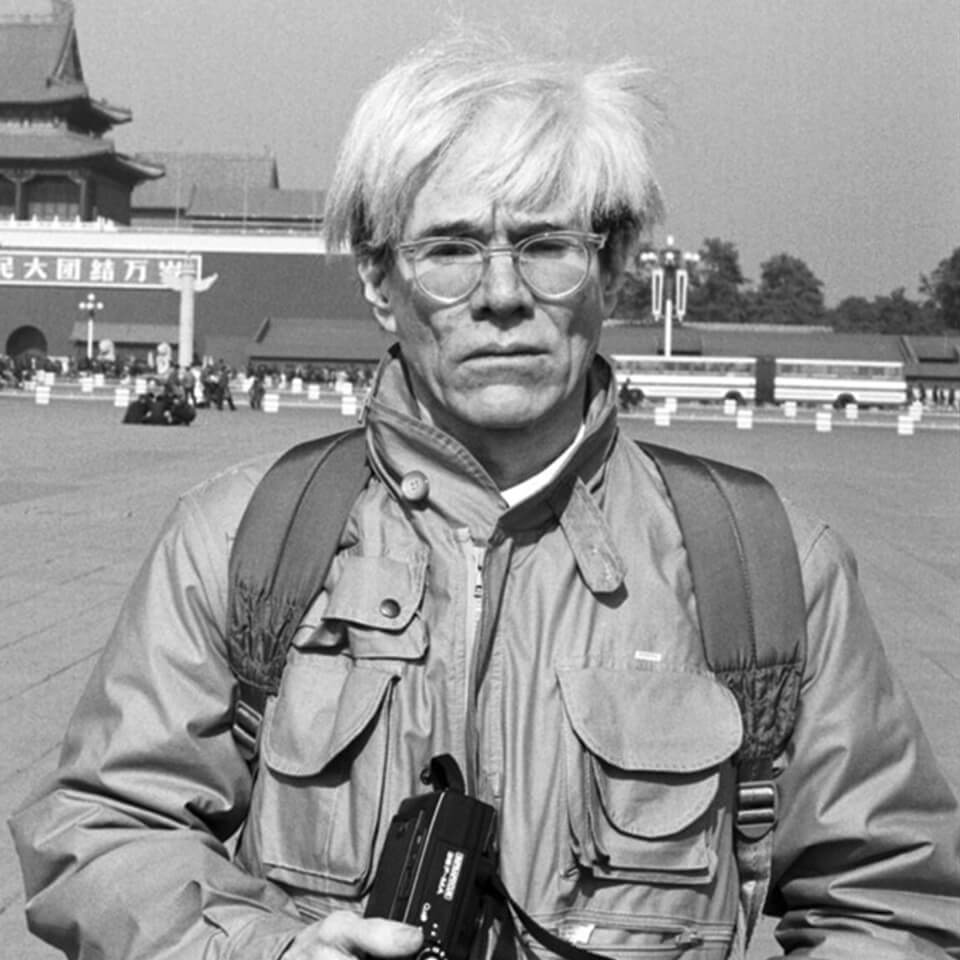

So what is it about Ai Weiwei? what makes him, according to western eyes, the “world’s most powerful man?” The answer lies in the west itself. Presently fixated on China, the West would surely invent Ai on the off-chance that he didn’t already exist. China may after all become the most powerful country on the planet. It must therefore have an artist of practically the same calibre to hold up a mirror both to China’s failings and its potential. Ai, whose name is pronounced as eye way-way fits in perfectly to fulfil this role. Having spent his developmental years as a craftsman in New York during the 1980s, when Warhol was a god and conceptual and performance art were dominant, he knows how to blend his life and art into a challenging and politically charged execution that characterizes how we see modern China. He’ll utilize any medium or genre – from sculpture, ready-mades, photography, performance and architecture to tweets and blogs to deliver his pungent message.

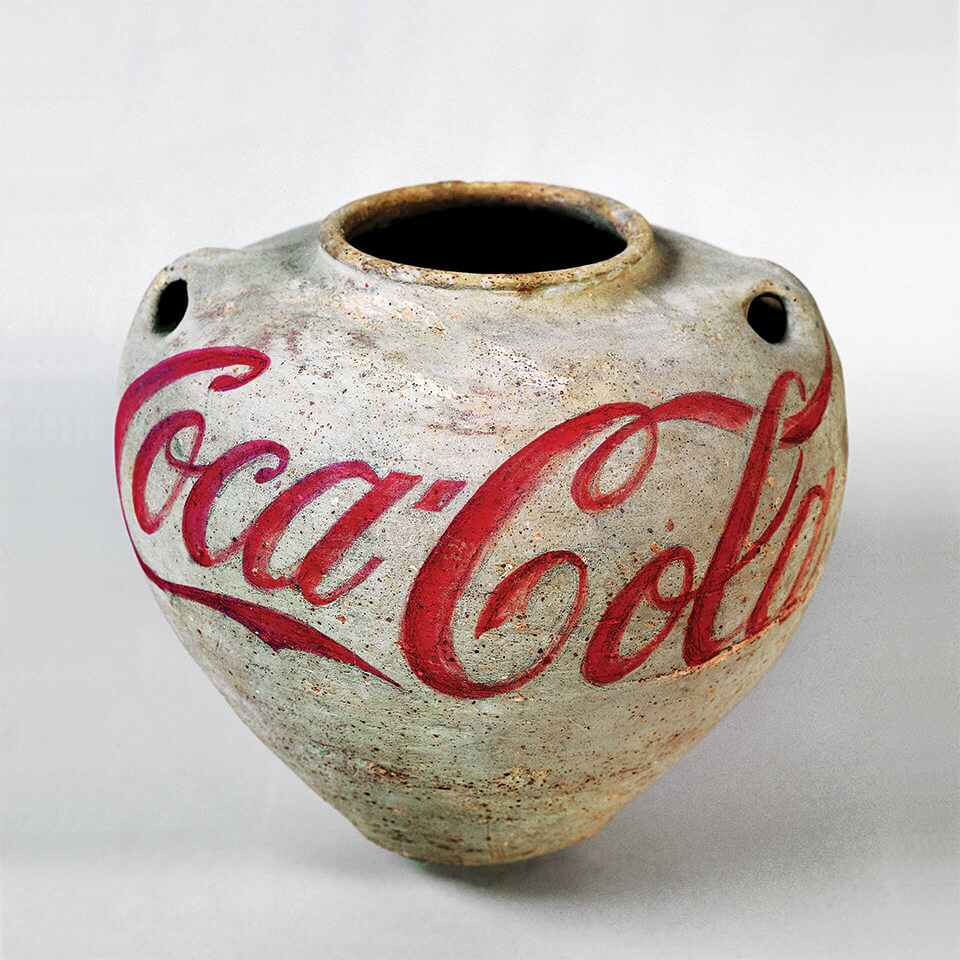

His persona, just like Andy Warhol’s, is an integral part of his art which cannot be separated. This draws power from the fact that artists in modern culture perform contradictory roles, the foremost of which are those of martyr, preacher and conscience. Not only has Ai Weiwei been harassed and jailed by the Chinese government, but he has also additionally persistently demanded an explanation from the Chinese routine; he has made a list that incorporates the name of every one of the more than 5,000 schoolchildren who died amid the Sichuan quake of 2008 as a result of shoddy schoolhouse development. If that’s not all, he’s also adopted a very Dada-inspired role of revolting against government-run organisations and the government itself. In a standout amongst his best-known photos, he gives the White House the finger. Not least, he is a sort of visionary artist. He cultivates the press, excites remarks and makes displays. His most successful work, Sunflower Seeds – a work of dreamlike power that was a sensation at the Tate Modern in London in 2010, comprises 100 million bits of porcelain, each painted by one of 1,600 Chinese skilled workers to look like a sunflower seed. Since porcelain is synonymous with the land of China, Ai Weiwei manipulated the traditional methods of this craft, one that has been China’s most prized export. This installation accurately articulates the “Made in China” phenomenon and the geopolitics of economic and cultural exchange in today’s times. An accurate response to this is, as Andy Warhol would say, in high deadpan, “Wow.”

Having built up himself as one of the world’s most well known and controversial artists, Ai Weiwei has now transported his abilities to the film world for “Human Flow”, a moving and significant interpretation of the ongoing global refugee crisis. This influencing narrative sees Ai move between camps all around the world, concentrating on the human condition en route – and the results, unsurprisingly, are not pretty. We had the delight of taking a seat with him to talk about why he feels sympathy is painfully ailing in current society. When asked about why he feels that compassion is lacking in today’s society he says,

“This crisis is maybe the biggest challenge we’ve faced since World War Two. It’s a challenge to our notion of freedom and democracy. Both sides are not very well prepared, the intellectual argument is still not there. These double standards have been there for a very long time, and eventually, it comes to haunt us. It starts to question the essential meaning of our existence….With this film, I was never eager to have it as an exhibition, because even though my shows always break records, it’s still in the art circle. This kind of topic needs to face the real public – immigrants, old people and young people who want to know the world. I’m an artist, but in my daily life, I’m passionate and want to get involved in awkward situations, something unfamiliar that could put me in danger. The media have become extremely exonerating about the tragedy, leaving no space for people to think and react and come to a more rational way to examine humanity. We wanted to make a different film which has a larger perspective that covers the total condition of humanity today.”

A question of major relevance that is not usually asked is whether Ai Weiwei as an artist is more than just a contemporary phenomenon. Is his artwork Sunflower Seeds more than just a passing headline? Will he ultimately matter to China and to the future as much as he does in today’s western art world?

The artist in exile now lives in Caochangdi, a small village in suburban Beijing that is often preferred by artists. Here, he regularly meets with visitors and followers who come to pay homage his refined vision of a better China. The 55-year-old artist who seems to be astonished about his prominence every time he’s asked about it says, “The secret police told me everybody can see it but you, that you’re so influential. But I think their behaviour makes me more influential. They create me rather than solve the problems I raise.”