Should a simple attribution have the ability to decide if a masterpiece is worth a large number sum of money be it a few hundred thousand or even millions? How dependable are the supposed specialists when they can be so effectively tricked by master forgers? For what reason do forgers’ works hang in world-renowned museums and galleries under other artists names and yet can’t find himself a viewing audience when he signs the works with his own name? Is the art market ludicrous, and do collectors urge fellow buyers to exploit them? These questions undoubtedly factor heavily when it comes to discussing the aspect of art forgers in the art market.

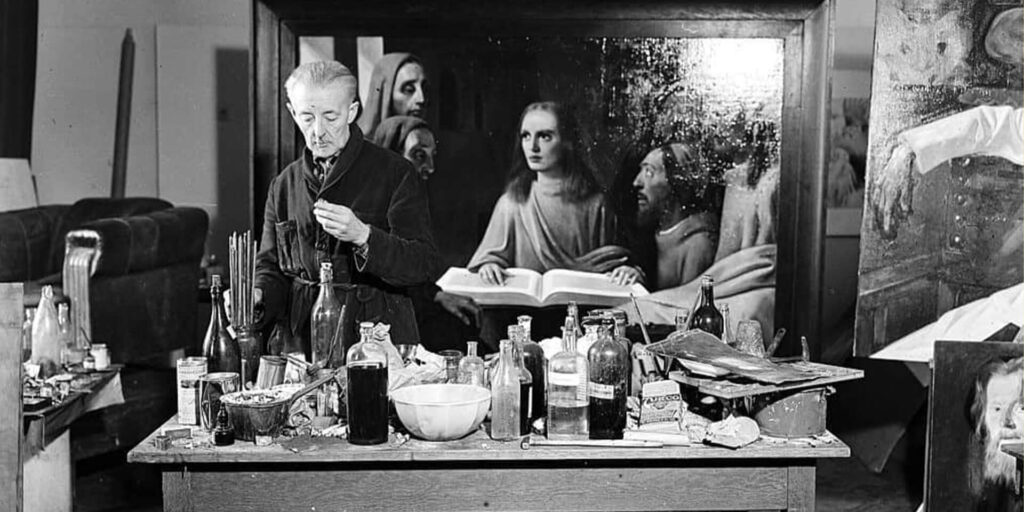

In many cases, it is up to the art dealer to determine a work’s authenticity. When authenticity is found to be a fake, a dealer may quietly remove the piece and either sell it back to the forger or discard it. While dealers now and again sell forged works accidentally, it is not common for a seller to be a specific forger’s distributor. What made seller John Drewe fruitful, were the false provenances that he wove for his forger, John Myatt, so as to make his false works seem real. He likewise sold pictures of imitations to prominent art institutions. By the end of it, Drewe made a profit of $2,940,000, though Myatt made only $165,000. Be that as it may, the two were captured and heavily fined for their wrongdoings. For this situation of fraud, it was the seller who motivated the artist to resort to illegal ways so as to turn a greater profit.

There are two ways to determine is a piece of art is the real, or if it has been forged. The first way is by using a more subjective method known as Stylistic analysis. This form of authentication relies on of art historians who use their highly specialised knowledge and understanding of the uniqueness and the progression of the artist’s style to conclude whether a piece of art is authentic or not. The second method, Technical analysis, utilizes equipment such as microscopes to view the oxidized cracks of oil paintings, or the extra layers on ancient glasses. This technique is used to see if there are parts of the artwork that have been artificially induced.

However, since falsification is an art all by itself, specialists are most likely unable to conclusively prove that an artwork is a fake only on the basis of visual examination. This is when a scientist is asked to step in and take charge over the artwork. Utilizing cutting systems and techniques, including instrumental analysis and imaging, scientists and conservators can do their own detective work in the art world. When authenticating a work of art, one of the major things that is evaluated by scientists is whether or not it’s material composition matches what is known to have been available and used amid the timespan in which it was supposed to have been created by the artist. This verification is often made by chemically analyzing pigments, colors and the main binding medium of the paint.

Despite popular belief, there is a major distinction between the identification of imitation versus the authentication of artworks. Science is generally adept at delivering proof of forgery but often is equally poor at proving authenticity. The essential explanation behind these gross contrasts is that connoisseurship and art history are all the more unequivocally engaged with the procedure of validation than scientific study, testing, and analysis. There is additionally a well-noted absence of substantive cooperation between art preservation experts, researchers, scientists, and art history specialists.

Issues emerge when a community of curators is approached to consider works that don’t so effectively “fit” into a defined “art period” or a “particular style”. Experts frequently will just acknowledge the best works of an artist and markdown works that are results of the artists’ evolutionary phase – the less accomplished works. Scientific and technical evidence is imperative in order to elevate the process of authentication.

“You know the [artist] had some choices in terms of what materials they used, and how they combined them,” says Aniko Bezur, conservation scientist and director of scientific research for the Technical Studies Lab at the Yale Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. With this kind of data, scientists and analysts can determine whether or not the particular material was available to the artist during his time and when the artwork was being created. Technological advances also enable scientists to gauge whether the chemical composition of the materials used for the painting process is consistent with that of other painting made by the same artist in question. Anachronisms also indicate whether an artwork is forged or not.

The equipment that these ‘art scientists’ or ‘conservation specialists’ use is just as applicable to the study and analysis done by cell biologists and chemists to study compositions in detail. Equipment used for artwork analysis can range from electron scanning microscopes to gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy. Of these, the former machine produces images of the surface of the artwork by taking microscopic samples and projecting on them a focused beam of electrons which can then map the elements present in the paint, varnish, etc. while the latter two are used to study the more organic components of the objects.